ARTICLE AD BOX

Ben Chu, Tom Edgington, Rob England and Lucy Gilder

BBC Verify

BBC

BBC

When it comes to reducing UK immigration, there have been plenty of promises and targets from successive governments over the last 15 years, but the numbers remain high.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer is now pledging to "take back control of our borders", promising tighter rules to bring down the numbers "significantly".

BBC Verify examines the measures set out by the government and the challenges ahead.

What's happened to the numbers?

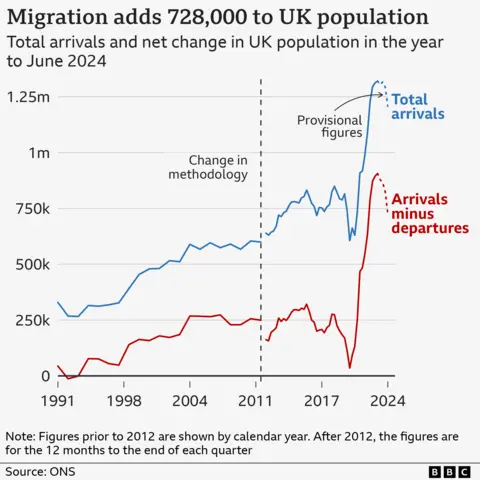

Migration levels have hit "unprecedented levels" in recent years, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Net migration to the UK - total permanent arrivals minus total permanent departures - reached a record 906,000 in the year ending in June 2023 and then fell to 728,000 in the year ending in June 2024.

The continued high levels persist, despite previous government efforts to bring the numbers down. For example, in 2010 the Conservatives pledged to reduce net migration to the "tens of thousands".

Annual net migration is expected to come down to about 315,000 by the end of the Parliament.

That's according to the central forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) - the independent body that scrutinises the public finances.

That estimate, however, would still be higher than most years in the past decade.

What's been driving immigration?

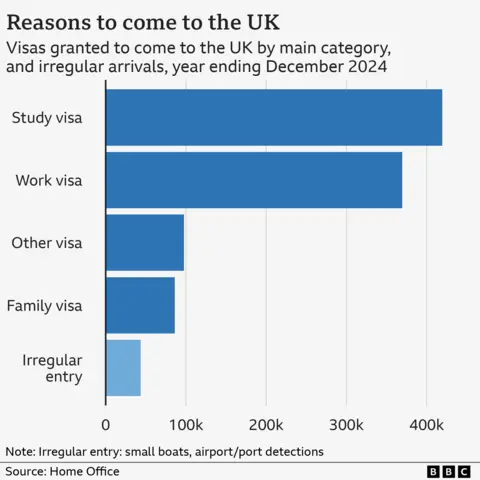

The vast majority of migrants come to the UK for study or work.

And many of the work visas have been for people coming to do jobs in health and social care.

However, applications for health and social care visas have come down sharply in the past two years after the rules were tightened by the last Conservative government and this decline will ultimately feed into the official net migration statistics in the coming years.

Does immigration help economic growth?

There's been much discussion about the link between immigration and economic growth.

The White Paper - which sets out the government's plan - says the UK economy needs to wean itself off a reliance on cheap overseas labour.

While taking questions from journalists, the prime minister claimed the idea immigration leads to higher economic growth "doesn't hold".

Economists do not agree about the exact impact that simply adding more people to an economy has on growth and prosperity.

New arrivals might increase the country's overall level of economic activity - measured by GDP. But on a per-person basis, GDP could be stagnant or falling. Also a larger population puts more pressure on demand for public services and housing.

However, if immigrants are filling important gaps in the labour market which would otherwise not be filled - especially jobs that require specific skills - then economists generally think that immigrants can boost GDP per head and general prosperity.

The OBR says that increased migration generally increases economic growth but "the size of this impact and the effect on per person living standards is highly uncertain".

The OBR's point about growth per person is important because the government has made growth of this measure a key priority.

Growth per person fell in 2023 and was flat in 2024.

What about social care?

There are gaps in our labour market which have been substantially filled by migrants in recent years, most notably social care.

And there were still estimated to be 131,000 vacant posts in adult social care in England in 2023.

Care providers argue stopping them recruiting from overseas will likely make that gap bigger.

Non-immigrants could theoretically fill many of these posts and working-age people who are economically inactive could potentially be deployed in this sector if they could be encouraged and helped into work.

Yet the main barrier to recruitment in social care has been the level of pay, which is currently too low to attract sufficient numbers of British workers.

Amy Clark, commercial director of a Cornwall care home chain, told the BBC that the measures could cause challenges because "recruiting locally is very, very difficult".

The government could increase the levels of pay in social care, but that would leave them under pressure to increase grants to local authorities and potentially raise taxes to fund it.

Problems with social care recruitment were also highlighted by Madeleine Sumption, deputy chair of the Migration Advisory Committee.

"We've seen widespread reports of exploitation, people coming in who are quite vulnerable earning very low wages.

"So I am not surprised the government has chosen to close overseas recruitment because it's caused them so much difficulty," she said.

What about universities?

Overseas students have been a major contributor to levels of net migration in recent years.

But they are also a significant source of funding for UK universities.

A large reduction in overseas students numbers would undermine the finances of many universities and a number are already in severe financial difficulties.

The government wants to monitor more closely how universities recruit international students.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Overseas students have been a major contributor to levels of net migration in recent years.

It is also proposing a limit on the time international students can remain in the UK after graduating. Foreign students would only have 18 months to look for a job, down from 2-3 years previously.

Universities UK - which represents 141 universities - has urged the government "to think carefully" about the impact of its measures.

If overseas student numbers did fall, the government could make up the shortfall in universities' revenue by increasing central government grants but, again, that could require an increase in taxes.

Alternatively, it could further increase domestic students' tuition fees, although that would also be contentious.

What about skilled migrants?

The government says it still wants to attract high-skilled individuals "who play by the rules and contribute to the economy".

However, the PM also stressed that some parts of the economy are "addicted" to importing cheap labour, rather than investing in training UK workers.

As an example, Sir Keir said the number of engineering apprenticeships had fallen in recent years, while visas for overseas workers in this area had gone up.

Figures in the government's new immigration plan show that the number of UK work visas issued for engineering professionals rose from 3,427 in 2021 to 5,495 in 2024.

Meanwhile, the number of new apprenticeships in engineering in England fell from 26,970 in 2021-22 to 18,520 in 2024-25.

But if the government wants many more home-trained engineers that will likely come with a cost in terms of a higher training budget.

While that investment could come partly from firms, it could also mean more public spending and possibly tax rises.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, total public spending on adult education and skills has fallen by 24% in real terms since 2010.

Reacting to the government's proposals, Make UK - which represents manufacturers - said firms are being forced to recruit overseas staff because domestic skills training is "fundamentally flawed".

"Without access to skilled labour in the UK, manufacturers cannot take advantage of the opportunities presented by the recent trade agreements with India and the US and deliver the growth we all want to see and the economy needs", said CEO Stephen Phipson.

Additional reporting by Anthony Reuben

5 hours ago

5

5 hours ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·