ARTICLE AD BOX

By Ben Wright & Peter Snowdon

BBC News

What would Francis Urquhart have made of today's MPs?

Before Netflix's Frank Underwood there was Francis Urquhart - the menacing, fictional Tory chief whip from the original BBC House of Cards series.

In the TV adaptation of Michael Dobbs's novel, Urquhart snarls that his job is to "put a bit of stick about - make 'em jump".

Corralling MPs to do what he wants with coercion, flattery and threats. A pantomime villain and a master of the dark arts of whipping.

It's all gloriously implausible. Or is it?

Whipping has been the hidden wiring of parliamentary life for at least two centuries. Some have compared their work to city sewers - crucial, but best not seen up close.

The term itself might sound a bit ridiculous - a centuries-old reference to hunting with hounds - but the whips bring order to political parties at Westminster.

At its most simple, government whips have the job of ensuring their MPs vote for legislation. Opposition whips assemble their parliamentary forces against the government's plans.

But in recent months, their methods and effectiveness have been in the headlines. In January, William Wragg, a Conservative MP who chairs the Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, claimed Tory whips had gone too far.

Whipped will be on BBC Radio 4 at 20.00 on Monday 28 February and available later on BBC Sounds.

He alleged that MPs suspected of wanting to remove Mr Johnson had been threatened with the removal of government investment in their constituencies.

It was a claim the Metropolitan Police decided not to investigate and the prime minister said he had seen no evidence to support it.

But Mr Wragg claims he does not regret his actions. "I felt compelled to speak out as a means, if anything, to prevent that kind of behaviour from continuing," he says.

His intervention came at a dicey moment for Mr Johnson, with speculation swirling about his leadership and a potential revolt by Tory backbenchers.

In February the prime minister appointed a new chief whip, Chris Heaton-Harris, in a clear attempt to repair relations between Conservative MPs and No 10. Will it work?

Shredded loyalties

"I think whether it does or doesn't depends less on the Whips' Office and more on whether the prime minister listens to them," says Conservative MP Mark Harper, a former chief whip himself and one of the leading rebels against the government's Covid regulations during the pandemic.

In December, nearly 100 Conservative MPs defied their whips to oppose the government's plans. It was the biggest rebellion of Mr Johnson's premiership and the latest indication that party discipline and the power of the whipping system appear to be weakening.

What was also startling about the December rebellion was how many newly elected Conservative MPs joined in. One was Miriam Cates, who represents Penistone and Stocksbridge - a red wall seat in South Yorkshire.

"We're very close. We've got a relationship that's been forged through a difficult period of history," she says. "I mean, Covid has been such a challenge. And so we very much drew on each other for support, albeit over WhatsApp, during that time.

"So there's probably a kind of closeness that we've got because of that."

For many MPs, WhatsApp is now the main way to communicate with colleagues. It makes it easier for them to organise and scheme away from the prying eyes of party whips. It's another reason their grip could be loosening.

The breakdown in whipping did not begin with the current political crisis. The paroxysm over Brexit shredded party loyalties and caused problems for the whips on both sides. Rebelling became routine and made life for the whips a nightmare.

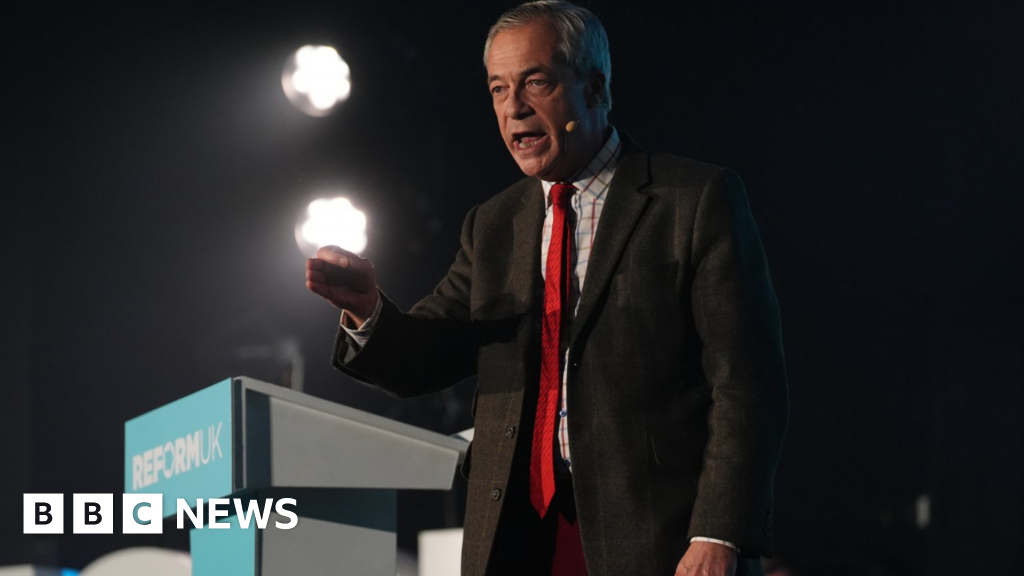

Image source, PA Media

Image caption,It's Chris Heaton-Harris's turn to bring order to Tory backbenchers

The ultimate sanction against an MP who repeatedly defies their whip is to remove it altogether. Cast outside the parliamentary party, they no longer receive weekly instructions on how to vote.

In September 2019, Mr Johnson stripped the whip from 21 of his own MPs when they sided with opposition parties to block a no-deal Brexit.

Former minister Caroline Nokes recalls how it felt. "When I got the voicemail from the chief whip, it wasn't a surprise," she says. "I still felt a little bit sick. But the following morning I got up, looked in the mirror and felt that I had done the right thing."

For Ms Nokes, who has since had the whip restored, the experience was "liberating". What party whips do not want are free-thinking MPs making their own decisions on big issues.

But an MP who has rebelled against their party once is quite likely to do it again and this is why whipping is getting harder.

Incredibly, 201 Conservative MPs, more than half the parliamentary party, have rebelled against their government on a big vote since 2017. It's a huge number by historical standards.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Losing the party whip was "liberating", says Conservative Caroline Nokes

Labour has also had its share of difficulties. When its MPs overwhelmingly rejected Jeremy Corbyn after the EU referendum, the opposition whips' office went into survival mode.

The Labour leader survived to fight another day, but that did not quell his fractious MPs.

"It was a case of whether the whole parliamentary party would fall to pieces," says whip Mark Tami.

Current and former whips say it would be chaos if MPs weren't marshalled around the party colours. But it's also clear backbenchers are ready to bridle against their whips, rebel on issues they disagree with and call out some tactics.

"You've got MPs acting much more as individual agents, much more conscious of working to represent their constituents, and more sceptical, perhaps, about what a career of being promoted as a minister might look like," argues Bronwen Maddox, director of the Institute for Government think tank.

If she's right, and the old ways of whipping MPs into line are breaking down, it's a huge challenge to the way UK politics works.

4 years ago

88

4 years ago

88

English (US) ·

English (US) ·