ARTICLE AD BOX

By Phil Mercer

BBC News

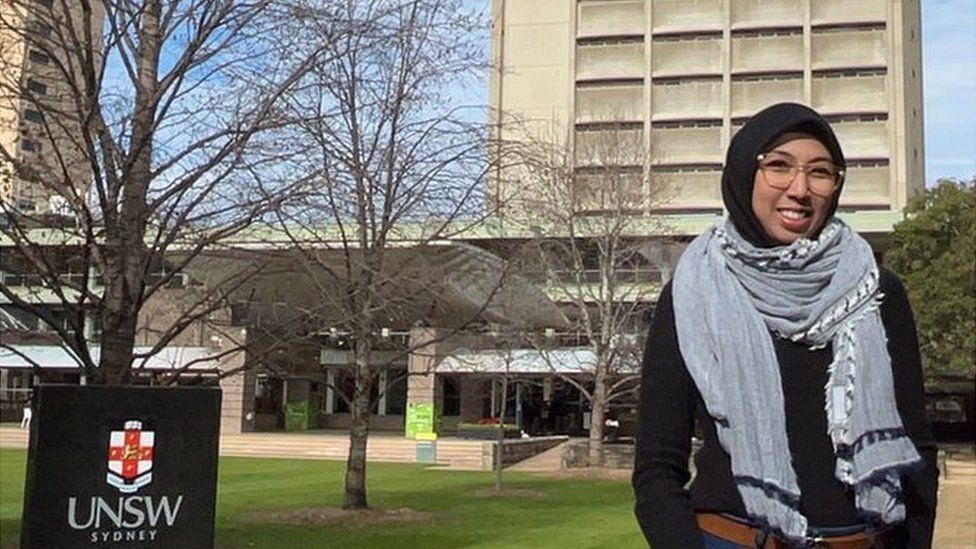

Sari Puspita Dewi arrived at the University of New South Wales in December 2021

"Saya cinta Australia!" says Indonesian student Sari Puspita Dewi.

"I love Australia! It is my dreamland to live and to study."

The PhD scholar from Jakarta has an electric enthusiasm for Australia that belies the country's often-lukewarm economic relationship with her homeland Indonesia, its giant neighbour to the north.

Culturally different, but geographically close, the two countries have collaborated on border security and counter-terrorism, and share a nervousness about the rise of China, but the commercial relationship has been underdone.

Pre-Covid, the holiday island of Bali was awash with carefree Aussies, but much of the vast Indonesian archipelago, from Sumatra to Sulawesi, often remains unnoticed.

Indonesia, the world's largest Muslim nation with a population of 270 million people, doesn't even make it into the top ten of Australia's most lucrative trading partners.

"It's hard to think of two neighbouring countries, each with economies in excess of a trillion dollars, that trade so little with one another," says Leigh Howard, the head of Asialink Business at the University of Melbourne.

"The extent to which international investors have made real commitments in Indonesia over the past decade - not just China and major partners such as Japan and Korea, but Europeans, Emiratis, Singaporeans, and even Canadians - strongly suggest Australia is not seeing opportunities that others do."

Image source, Alisha Reading

Image caption,One sector where trade is flowing between the two countries is grain crops. Indonesia is an important export market for Australian grain farmers

Language and cultural barriers have hindered Australian engagement with Indonesia. There have been easier pickings elsewhere for entrepreneurs in Singapore, the Philippines and the Pacific.

"More small (Australian) businesses go to Fiji than Indonesia. I think Indonesia has traditionally been a closed market," says Tim Harcourt, chief economist at the University of Technology Sydney. "Generally Indonesia is a bit like the United States or Brazil - they think about the domestic market first rather than a place like, say, Singapore, that's very much open to trade and investment from the global economies.

"Indonesia was never this low labour cost place that China, Vietnam and Bangladesh were. Indonesia's all about being a large middle class [that's fuelling] a domestic economy."

But that could all be about to change if Jennifer Matthews has her way.

She's the national president of the Australia-Indonesia Business Council and is evangelising on Indonesia's new openness in a travelling roadshow across Australia in partnership with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

It has visited Darwin in the Northern Territory, which is closer to Jakarta (2,700km) than it is to Canberra (3,100km), and will soon head to Sydney to promote the digital economy.

"The time is right," she says of accelerating Australian trade with Indonesia to boost jobs in the post-pandemic recovery. "There is definitely an opportunity to grow this relationship. We can see the transformational change that is taking place in Indonesia right on our doorstep."

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese visited Indonesia shortly after being elected

In July 2020, the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IA-CEPA) came into force.

"By some estimates, Indonesia will be the world's fifth largest economy by 2030, and IA-CEPA ensures that Australia is well-placed to deepen economic co-operation and share in Indonesia's growth," DFAT said. The pact aims to jettison tariffs while nurturing commerce.

Anthony Albanese, the recently elected Labor prime minister, made a trip to Indonesia within a few weeks of winning the election on 21 May.

It was an unequivocal statement that the new management in Canberra coveted the relationship and wanted trade to bloom.

"The road to Jokowi's (the popular name for Indonesian President Joko Widodo) heart will be business and investment," Prof Dewi Fortuna Anwar, from Jakarta's Research Centre for Politics, told the Australian Broadcasting Corp. "The ball is in Australia's court," she added.

The key lies with innovation and services.

Agriculture, resources, energy, education, training and healthcare are all sectors with potential, along with expertise in renewable power technology.

Tim Harcourt's advice is for Aussie firms to look beyond the sprawling Indonesian capital for fertile ground.

"In West Java, I met a lot of South Australian, defence and agricultural companies that have done quite well. Yogyakarta, the gaming and IT centre of central Java is another opportunity. So, think about the archipelago as a number of very different, distinct markets rather than just zooming in to Jakarta."

Image source, GrainGrowers

Image caption,"There is a maturity in our trading relationship with Indonesia," says farmer Brett Hosking

Other sectors have been quietly going about their business with Australia's giant neighbour to the north.

"Indonesia is by far our largest trading partner when it comes to exports of Australian wheat. It's a pretty good relationship at the moment," Brett Hosking, chair of GrainGrowers, an industry group, and a farmer in Victoria, told the BBC News website. "We have to be sensitive to the cultural uniqueness of each country, so understanding that Indonesia is a largely Muslim country. If we make the extra effort to do so we build a much stronger relationship."

Australia's biggest trading partner by some considerable distance is China. Its appetite for resources, most notably iron ore, made Australia rich, but geopolitical tensions have surfaced in recent years. Trade has suffered, too, with restrictions imposed on various Australian exports.

Brett Hosking's personal interaction with Indonesian flour millers and government officials has helped to ensure that ties remain on a sound footing.

"We've had a disagreement with China around barley not so long ago. That has had an impact on our market. But disagreements will come and go. I would say there is a maturity in our trading relationship with Indonesia," he says.

Sari says she would like to stay in Australia while still contributing to Indonesia

Indonesians have a long history of migration to Australia. Increasingly, its super young population wants to savour the education and lifestyle offered by its multicultural southern neighbour.

With a YouTube channel and a following on social media, PhD student Sari Puspita Dewi, who arrived at the University of New South Wales last December, is doing her bit to encourage her compatriots to join her.

"So many people get inspired to study in Australia. It is near to Indonesia. They don't feel too homesick," she says. "I was so happy when I was selected [for a scholarship]. If I have a chance, I want to live here longer, but of course on behalf of my country and contribute to Indonesia."

2 years ago

46

2 years ago

46

English (US) ·

English (US) ·