ARTICLE AD BOX

By Sharanya Hrishikesh

BBC News, Delhi

Image source, Facebook/Devbhoomi Raksha Abhiyan

Image caption,Some Hindu leaders called for violence against Muslims in December

Is it really easy to get away with hate speech in India?

A spate of recent incidents in the days leading up to the Hindu festival of Ram Navami on 10 April would suggest so. The festival was marked by incidents of hate speech and even violence in some states.

In the southern state of Hyderabad, a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lawmaker - who was banned by Facebook in 2020 for hate speech - sang a song with lyrics that said anyone who didn't chant Hindu deity Ram's name would be forced to leave India soon.

Days before that, a viral video showed a Hindu priest allegedly threatening to kidnap and rape Muslim women in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. Police registered a case only after a week when the video of the speech generated outrage.

Around the same time, Yati Narsinghanand Saraswati - another Hindu priest who is out on bail in a hate speech case - made another speech in the national capital, Delhi, asking Hindus to take up arms to fight for their existence.

The speech - at an event for which the Delhi police said the organisers didn't have permission - violated one of Mr Narsinghanand's bail conditions but no action has been taken against him yet.

Hate speech has been a problem in India for decades. In 1990, some mosques in Kashmir broadcast inflammatory speeches to whip up hate against Hindus, triggering their exodus from the Muslim-majority Kashmir Valley. The same year, BJP leader LK Advani spearheaded a movement to construct a temple in the northern town of Ayodhya - leading to Hindu mobs razing the centuries-old Babri mosque and sparking deadly communal riots.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,The rise of social media has helped amplify hate speech

But the scale of the problem has accelerated in recent years, with Indians being regularly bombarded with hateful speech and polarising content. With social media and TV channels amplifying remarks and tweets even by minor politicians - many of whom find it the easiest way to make headlines - the hateful rhetoric seems "pervasive" and "non-stop", as political scientist Neelanjan Sircar puts it.

"Earlier, hate speech would usually rise in the run-up to elections. But now, with our changed media landscape, politicians have realised that something offensive said in one state could be magnified for direct political benefit in another state immediately," he says.

News channel NDTV, which in 2009 started tracking "VIP hate speech" - offensive statements made by major Indian politicians including ministers and lawmakers - reported in January that such comments had risen manifold since Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu nationalist government came to power in 2014.

Several BJP leaders - including a federal minister - have been accused of getting away with hate speech. Some opposition politicians, such as parliamentarian Asaduddin Owaisi and his brother Akbaruddin Owaisi, have also been accused of giving hate speeches. Both deny the accusation and Akbaruddin Owaisi was acquitted in two hate speech cases from 2012 on Wednesday.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Opposition leader Akbaruddin Owaisi (centre) was acquitted in two hate speech cases this week

India has enough laws in place to check hate speech, experts say.

"But they require the executive to enforce them. And most of the time, they don't want to act," says Anjana Prakash, a senior advocate who had filed a plea in the Supreme Court seeking action against some Hindu religious leaders who called for violence against Muslims at a December event in Uttarakhand state.

India doesn't have a legal definition for hate speech. But a number of provisions across laws prohibit certain forms of speech, writing and actions as exceptions to free speech. This includes criminalisation of acts that could promote "enmity between different groups on grounds of religion" and "deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs".

The issue of hate speech has often come up before India's courts. But the judiciary has mostly been wary of imposing restrictions on free speech.

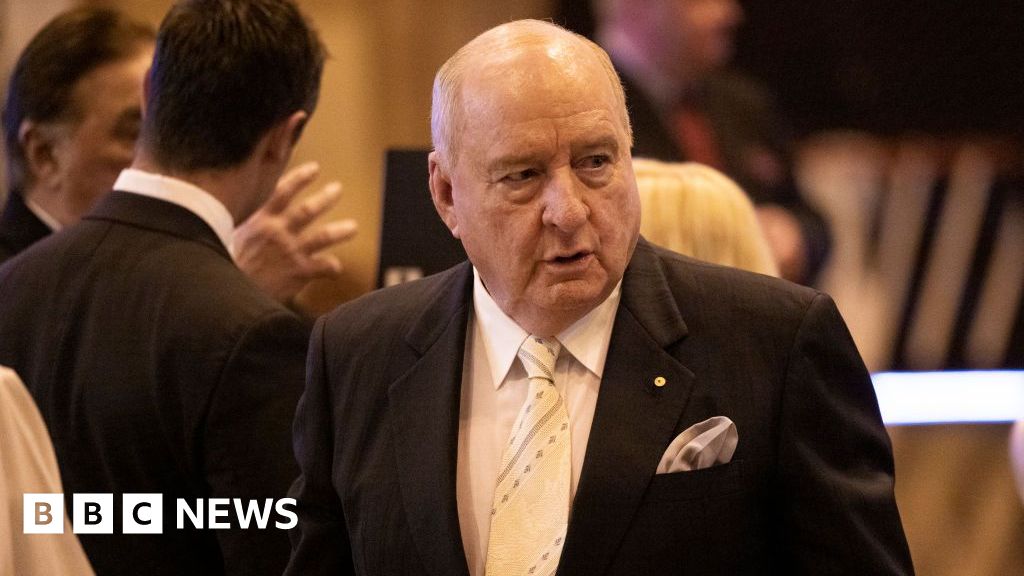

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Many BJP leaders, including a minister in Mr Modi's government, have been accused of hate speech

In 2014, while hearing a petition which asked the Supreme Court to issue guidelines to curb hate speeches made by political and religious leaders, the court recognised the adverse impact these could have on people but refused to go beyond the scope of existing laws.

"It is desirable to put reasonable prohibition on unwarranted actions but there may arise difficulty in confining the prohibition to some manageable standard," the court said. Instead, it asked the Law Commission - an independent body of legal experts which advises the government - to examine the issue.

In its report submitted to the government in 2017, the commission recommended adding separate provisions to the Indian Penal Code to specifically criminalise hate speech.

But many legal experts have expressed concern over the proposed amendments.

"The benefit of a law to specifically identify or broaden the definition of hate speech may be marginal when what would qualify as hate speech is already criminalised," says Aditya Verma, a Supreme Court lawyer.

The bigger concern, he says, is institutional autonomy. He cites the example of the UK, where police have fined top government officials - including Prime Minister Boris Johnson - for attending parties that broke Covid rules.

In India, however, it is not unusual for state institutions such as the police to be reluctant to do their duty because of political pressure.

"There may be legal grey areas, but what is more important here is the black-letter law that is not being implemented," Mr Verma says.

This "dereliction of duty", as Ms Prakash describes it, has serious consequences.

"Unless you punish a person who makes inflammatory speeches, how can the law act as a deterrent?" she asks.

There is also a larger, more painful cost to be paid when hateful rhetoric is normalised.

"When the environment becomes that unpleasant, people start getting so intimidated and scared that they think twice before engaging even in normal social and economic activities," Mr Sircar says.

"That is the real cost here."

2 years ago

90

2 years ago

90

English (US)

English (US)