ARTICLE AD BOX

By Mark Savage

BBC Music Correspondent

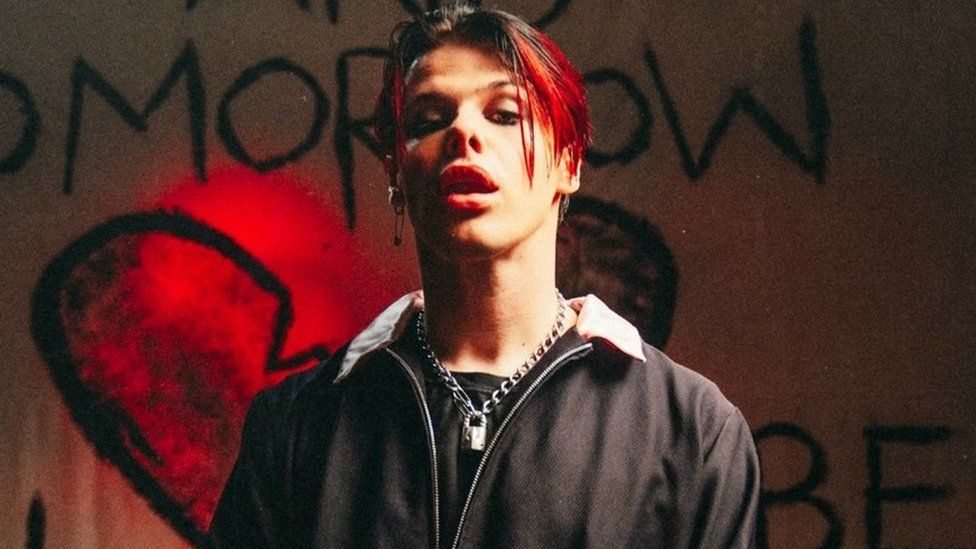

Image source, Tom Pallant

Image source, Tom Pallant

Mick Jagger said Yungblud "makes me think there is still a bit of life in rock and roll".

Two weeks ago, Yungblud got into serious trouble at Japan's Summer Sonic festival.

"I am very worried about the next performer," a compére told the audience in Osaka, moments before the singer took to the stage.

"Whatever he says, you must not mosh or shout."

Five minutes later... pandemonium.

Yungblud says he was unaware that Japanese audiences tend to be more restrained, with dancing frowned upon and applause reserved until the end of the concert.

"I just went on stage and screamed, 'Come on, jump!'" he recalls. "And it's so funny, they'd been so restricted all day, it was like they were unleashed. They were a bottle of Coke and I dropped two Mentos in - Bang!

"It was beautiful but I did get in trouble. Everyone gave me this disapproving stare, like, 'What the hell was that?' And I was like, 'What did I do? Was I singing flat?' No one had told me the rules!"

Outside the venue, it was a different story.

"The young people were just like, 'Thank you, thank you, thank you so much.' Because everyone needed to release, everyone needed to feel freedom.

"And that's what it's about with Yungblud. It's about freedom."

This lofty pronouncement is typical of the singer-songwriter born Dominic Harrison.

To his mind, Yungblud isn't a just stage name, it's a movement. Over the course of three albums and hundreds of live shows, he's gathered a tribe of like-minded misfits who respond to his stories of alienation, depression and rebellion with almost religious fervour.

He doesn't call them fans. In fact he hates the idea, declaring, "If I ever become a rock star, the whole thing is flawed". Instead, it's a symbiotic relationship. As they found solace in his music, he found a sense of belonging in their kinship.

"I felt so lost and lonely as a kid," he says. "Walking down the street I felt alone, even if I was surrounded by 10 mates. And through this music, I got to find a community that would protect me."

"I open my chest up, I put my heart on a plate and I know people will look after it. Even if the rest of the world spits on it or treads on it, someone will pick it up and sew me back together."

Warning: Third party content may contain adverts

Occasionally, Harrison gets carried away with this train of thought. In 2020, he told The Guardian: "If you know Yungblud, the music is secondary," presumably giving his PR a heart attack. But he sticks to his guns to this day, downplaying the importance of his recent NME and MTV Awards.

"That stuff's okay," he says. "That sits on my shelf and I can put it on my wall but it doesn't light my soul on fire. What lights my soul on fire is creating a sense of belonging."

As if to prove where his loyalties lie, Harrison has invited my 12-year-old daughter to our interview after learning she's a fan. They immediately bond over fashion: He loves her shoes, she loves his jet black hair.

"My secret is," he says conspiratorially, "I put dye inside my conditioner, so every time I have a shower, I get a touch up."

My daughter tells him school is forcing her to cut her hair, after dying it over the summer. "I hate that," he recoils. "I think that's so terrible.

"I used to do it anyway, though. I was so naughty. I'd come in with a safety pin in my ear, thinking I was Johnny Rotten, like, 'Whatever, miss'."

At school in Doncaster, Harrison was criticised for his fashion choices, even by teachers, who would single him out in front of the class.

Home life was tricky, too. "We ran a family business so it was turbulent," he says. "If it went well, it was great. If it was bad, it was bad."

To escape, Harrison retreated into his imagination. "I was still playing war games 'til I was 15," he says. "Toy soldiers, all that jazz. Even now I'm like, 'pow, pow, pow,' on the tour bus."

He dreamt of becoming a drummer, a painter, a musician. Anything that could provide a creative release. "It made me feel free".

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,The singer has amassed a huge fanbase through relentless touring

By 16, he'd enrolled in a performing arts school, and was cast in the Disney TV musical The Lodge. But after one series, he quit to pursue music on his own terms, blending a frenetic cocktail of punk, emo, pop and indie, all delivered with a sneer worthy of Billy Idol himself.

His debut album, 21st Century Liability was recorded in a Soho basement "on toy keyboards, drum machines and weed". The songs explored the neuroses of his generation, from sexual inequality (Polygraph Eyes) and gun violence (Machine Gun) to his ADHD (Doctor Doctor).

At every turn, he says, he faced opposition. His record label boss "didn't get me", and he was advised not to release a song called Parents, in which a homophobic father meets a sticky end.

"The label said, 'Don't put that out. It's too aggressive. It'll never get played on radio'," Harrison recalls.

"And it never has been played on radio - but it's platinum in America and Australia."

That is very much the Yungblud story. Despite an impressive 7.5 million monthly listeners on Spotify, the singer isn't a fully mainstream proposition. His second album, Weird, entered the charts at number one, but dropped to 33 the following week - suggesting a passionate fanbase, but little interest from the wider record-buying public.

Even so, the success of Weird opened up a lot of doors. It's just that Harrison wasn't keen on what he found behind them.

"I had access to every studio I wanted, and every songwriter wanted to work with me," he says. "But I'd have all these American producers going, 'Oh, you're doing the rock thing? I could get in on that.'

"I'm like, 'Clear off. What do you mean, I'm doing the 'rock thing', like it's in inverted commas'?"

As his profile rose so, too, did the voices of his critics. He was accused of queer-baiting, of pretending to be working class, of being a record industry plant.

"Everyone was questioning my authenticity and it hurt me," he says. "People were harsher to me than they were in high school. It made my world turn inside out."

Image source, Tom Pallant

Image caption,"To self-title your third album is weird," says the star, "But when I was making it, I was like, 'I think I'm really understanding what Yungblud is'."

Stunned, he went back to his trusted collaborators Matty Schwartz, Chris Greatti and Jordan Gable, and poured all of his anguish into a new album.

Recorded in a bedroom (admittedly a bedroom in a Californian bungalow), it's Yungblud's most vulnerable and cohesive project to date.

A blistering lead single, The Funeral, finds the 25-year-old listing his failures and insecurities; and wondering if anyone would care enough to attend his wake. Memories, a duet with Willow Smith, is about letting go of childhood anxieties. And the emotionally-charged I Cry 2, finds him consoling a friend who's been through a brutal break-up.

"He was having a really emotional time but he couldn't talk about it and I was like, 'Bruv, it's alright. I cry too'," Harrison recalls.

"It's okay if you're feeling upset, if you're hurting. It means your soul is working, And I thought there was a really beautiful message within that."

The song also tackles the hatred Harrison received on social media over his "fluid" gender identity.

"Everybody online keeps saying I'm not really gay... And I spеnd most of my days wondering what the [expletive] do they want from mе?"

Lyrics like these aren't a "woe-is-me rock star story", he stresses. Instead, "it's a metaphor for the oppression millions of people feel". By speaking up and sticking together, he reasons, things can only improve.

"When I was 18, I was so furious at the world," he says. "I was so furious at the government, at Brexit. I felt so voiceless."

"But how can I be angry when I live in this community? I've realised the protection we have within each other."

Follow us on Facebook, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.

2 years ago

20

2 years ago

20

English (US)

English (US)