ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

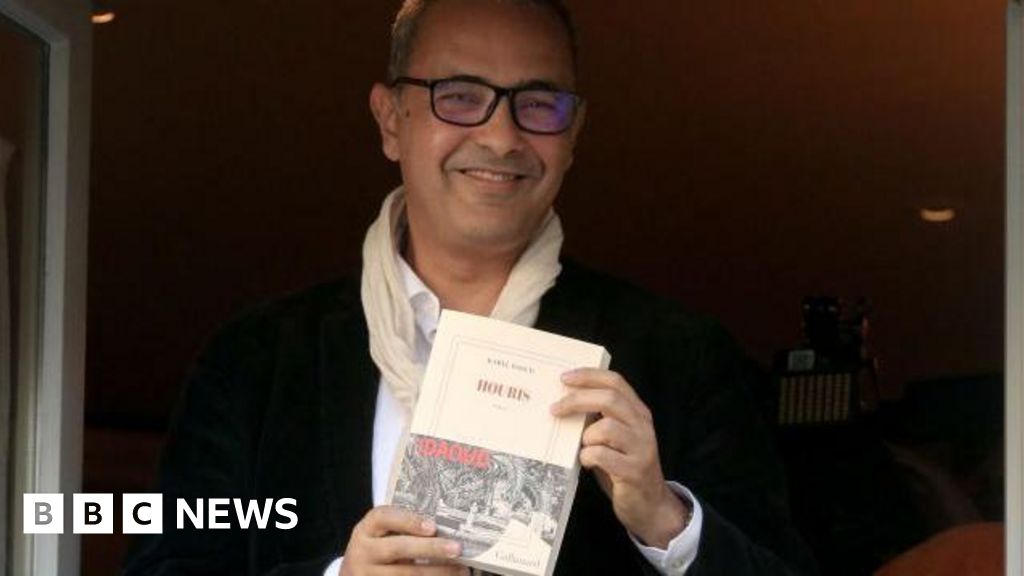

Thousands of unregistered guns were handed in after back-to-back mass shootings in Serbia

By Guy Delauney

BBC News, Balkans correspondent

Shock and horror might have been Serbians' first reaction to two mass shootings in as many days earlier this month. But outrage swiftly followed.

Tens of thousands of people attended two protests in the capital, Belgrade, with smaller rallies in other cities around the country.

They marched under the banner "Serbia Against Violence" and called for an end to what they viewed as a culture of violence which led to the shootings at a school in Belgrade and, the next day, around Mladenovac, south of Serbia's capital.

More protests will follow - and the government seems rattled. Senior figures have been talking down the numbers involved, as well as making plans for a "solidarity" rally of their own.

But there is one issue which both protesters and authorities seem to agree on: gun control.

"There is no pro-gun lobby in Serbia," says Bojan Elek, the deputy director of the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy and an expert on firearms issues in the country.

"There is a national association of gun owners - but nothing close to what they're doing in the US with the National Rifle Association (NRA)."

In the wake of the shootings, President Aleksandar Vucic swiftly announced what he called a "general disarmament" of the country. He declared a month-long amnesty for illegally-held weapons, with a warning of harsh consequences for anyone who held on to guns without a permit.

The president also has legally-held weapons in his sights. Mr Vucic has announced a moratorium on new weapons permits and a review of current gun licences.

All this would appear to be quite an undertaking in a country where the number of guns in circulation is, apparently, alarmingly high. In 2018, the Switzerland-based Small Arms Survey ranked Serbia third in the world for the number of weapons in private hands, with 39 guns per 100 people.

The public and political reaction to such a disarmament programme in the country which tops the list, the United States, can be imagined. In Serbia, says Bojan Elek, it has been a different matter.

The amnesty has been mostly positively accepted, he says, and by the second day of the amnesty, more guns and ammunition had been handed over than in the previous three amnesties put together.

"The number of illegal guns is definitely being reduced - even some weapons from World War II have been handed in. But we haven't got a credible figure of how many there were to start with, so it's hard to say how many are remaining."

Given the government's swift action to reduce the number of weapons in circulation and the lack of widespread objections to their proposals, the question is: why are tens of thousands of people still motivated to hit the streets in protest?

Political analyst Bosko Jaksic agrees that the weapons amnesty is not the bone of contention.

"The only thing which Vucic organised promptly was gun control. This is organised well and it works - so why should the demonstrators ask for such a measure when it already exists?"

Instead, the protesters are looking beyond the weapons and towards what they view as the root causes of the shootings.

The specifics include demands for the resignation of two senior government officials and the revocation of the licences of two pro-government broadcasters. But overall, protesters say they are most concerned about a culture of both rhetorical and physical violence which they believe has grown since the Serbian Progressive Party took power in 2012.

"We are surrounded by violence - in the public domain, political communication, parliament and television shows," says Belgrade resident, Aleks. "The culture of civilised conversation is completely lost."

Another protester, Milos, feels much the same way.

"The tragic events were a culmination of the violent methods - not necessarily physical - that they're practising in the media," he says.

Watch thousands gather for anti-gun march in Belgrade after mass shootings

Neither of these particular protesters believe that Serbia is in danger of emulating the levels of gun violence seen in the US.

"That narrative is mainly coming from government officials who are blaming 'Western values'," says Aleks. "What we're seeing has nothing to do with Western values, but values imposed on us by our own government."

Bojan Elek takes a slightly broader view.

"There is definitely some fear about emulating the US," he says. "But the government is riding this fear and trying to introduce problematic measures, like reducing the age of criminal responsibility to 12 and allowing police to enter homes without court orders."

The protesters' demands have yet to be met. But the pro-government broadcaster Pink TV has announced the cancellation of a controversial reality programme which has long been on the receiving end of criticism for its tacit approval of verbal and occasionally physical violence.

Meanwhile, President Vucic has talked down the significance of the protests - accusing opposition parties of using a national tragedy for their own benefit. That has not, however, stopped him from announcing his own rally at the end of this month, with a special meeting of the Progressive Party the following day.

"President Vucic has shown he's afraid of the street - of people gathering in Belgrade and other cities," says Bosko Jaksic.

"These meetings are polarising. Why not just go on TV instead of paying millions to transport and feed people you bring to Belgrade? It's a manifestation of glory instead of solidarity, not unifying but further dividing Serbia."

And that may be what brings more people on to the streets of Belgrade in the coming days and weeks.

1 year ago

18

1 year ago

18

English (US)

English (US)