ARTICLE AD BOX

Raghad never had a chance to say goodbye to her parents before they were deported to Syria

By Carine Torbey

BBC News Arabic, Beirut

There was some apprehension in the car as we drove across the mountains of Lebanon to reach the house of Raghad's aunt. Talking to a little girl who has just been separated from her family and who doesn't know when she will see them again risked being a very delicate task.

But as soon as we saw her, our anxiety eased. Raghad was dressed in bright clothes, with her hair tied up in a ponytail. She gave us an effortless smile and her eyes lit up. Her calmness reassured us.

Raghad barely spoke, so her uncle told us what had happened to her and her family. The young girl listened carefully. The only time she intervened was to correct him when he said she was seven and she insisted she was eight. A light-hearted debate ensued. A fun moment in a grim story.

Raghad is now living in a different country to her parents and never had a chance to say goodbye.

On 19 April, just two days before Eid al-Fitr, the Muslim celebration which marks the end of Ramadan, the Lebanese army raided Raghad's home.

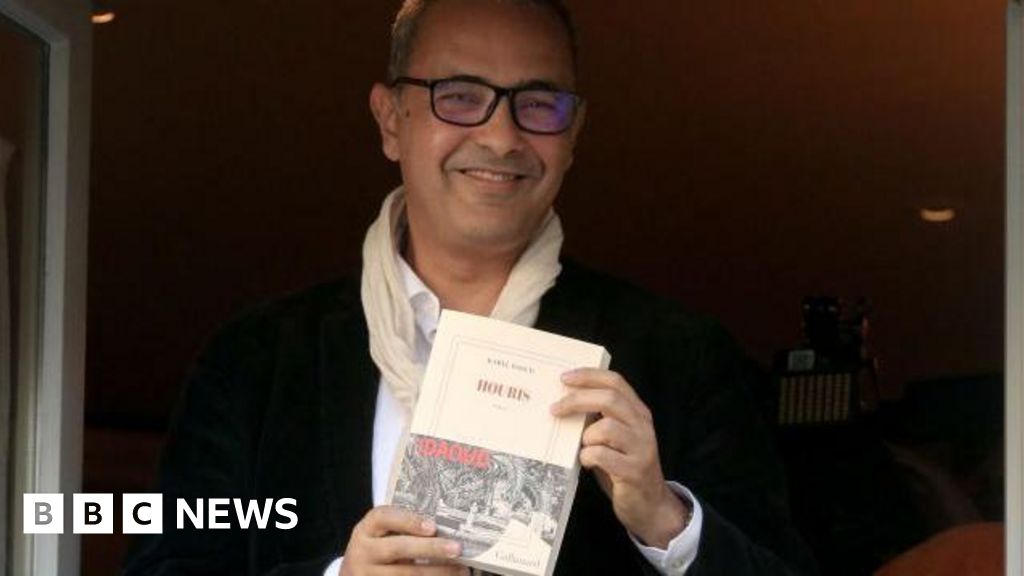

Raghad shows BBC reporter Carine Torbey the phone she uses to talk to her father

Her parents' documents had expired. Without any notice, they and Raghad's siblings were arrested and later deported to Syria.

"They told us to put our clothes on and take whatever precious belongings we have," her father told us over the phone.

It was around nine in the morning and Raghad was at school. Her father told us that he had pleaded with the army to let them wait for her return but they refused. Raghad came home from school and knocked on the door, but no-one opened. She burst into tears. "I was very scared," she said.

A neighbour called her aunt, who lives a short distance away and rushed over. Raghad now lives with her. The deportation of Raghad's family was part of an army crackdown on Syrians living illegally in the country.

Her family has been living in Lebanon for 12 years since the start of the conflict in Syria. Raghad was born in Lebanon, but her family is from Idlib in north-western Syria - a key location in the war and the last remaining stronghold of rebel forces.

"Imagine living in a country for 12 years just to be kicked out like this. We can't return to our town because of the situation there," says Raghad's father, whose identity we are protecting due to safety concerns.

Raghad's family is staying with friends in the Syrian capital, Damascus. I asked whether the family is trying to take Raghad to Syria, but they told me they would rather return to Lebanon. It won't be easy.

Large numbers of Syrian refugees live in informal settlements scattered across Lebanon

The Lebanese authorities, supported by what seems to be a rise in anti-Syrian sentiment across the country, say they want the refugees to return home.

Lebanon is hosting the largest number of refugees in the world when compared to the size of its population. Around 800,000 Syrians are registered with the United Nations, though the Lebanese authorities estimate the actual number of refugees to be more than double that figure.

Several times in the past decade, there have been waves of anti-Syrian sentiment and a tightening of laws and regulations targeting them. But this time, the debate seems different and there appears to be widespread agreement about sending them home.

The Lebanese say they can no longer bear the brunt of looking after so many refugees when they are facing one of the most severe financial and economic crises in recent history. They say Syrian refugees are making things worse by competing with them for scarce resources and services.

They also blame them for a rise in crime and for threatening a delicate demographic balance. High birth rates among Syrians are often highlighted in contrast to the low birth rates among the Lebanese to boost this narrative.

The outcry has pushed some local authorities to tighten regulations for Syrians.

The mayor of Bikfaya, Nicole Gemayel, defends the curfew imposed on Syrians in her town

The town of Bikfaya in the mountains above Beirut has imposed a curfew on them. "No-one in the world has welcomed the Syrians the way we did," says Mayor Nicole Gemayel in defence of the policy, which rights groups say is racist.

Supporters of the plan also point to the security situation in Syria, where there are currently no major military confrontations.

This ties in with political overtures towards the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, who is no longer considered a pariah by many governments in the region.

The Lebanese authorities say all these factors should bring an end to the refugee crisis. They also highlight what they describe as "illegal movements" back and forth across the border.

They say this "traffic" undermines the argument Syrians make that they fear for their lives back home. Meanwhile, the army says it's only following the rules when deporting Syrians.

Some prominent political voices in Lebanon also accuse foreign countries and international aid organisations of trying to keep Syrians in Lebanon, saying the aid the UN provides is an incentive to stay. The UN denies this and says any return of refugees should be voluntary because conditions in Syria are still not safe.

But for little Raghad, none of this debate matters. She misses her parents and wants to be back home with them.

1 year ago

117

1 year ago

117

English (US)

English (US)